I won’t give up on you

- 2017/03/29 18:28

Professor Soetanto has lectured in his home country Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia and China, after receiving impassioned calls from governments and related organizations in those countries. The passionate feeling he puts into his teaching has inspired beleaguered young people around the world; he is even being picked up by the media in those countries. Three students spoke with Professor Soetanto, who has returned to Japan after a long period away.

(photo :nikkie BP Mr sugano )

Q:Please tell us about your childhood and the details of how you came to Japan

A:Both my parents died when I was an infant, and I was raised by a very strict stepmother. With my weak constitution I was treated as a burden, so I have no fond memories of home. Being at home was unpleasant, so I began leaving early for school in the morning so I could help clean there. I started to be acknowledged by the teachers and everyone because of this; I then wanted to be acknowledged even more so I began to study harder and teach classmates and children in my neighborhood how to study. However, in 1965 when I had just started my first year in senior high school, the new government that had arisen out of the anti-Communist Party coup d’état (known as the 9.30 Incident) closed every school for Indonesian-Chinese children around the country, so we could no longer receive an education. I had no choice but to begin helping in my older brother’s business selling electronics, and while doing that I started my own repair business. Not only did that business become a huge success, my older brother was also able to lead a prosperous life, and it was from these economic reasons that I, despite being unable to go to high school and university, felt an uncontrollable urge to study more.

With my ambitions to become an engineer, I was naturally fascinated by Japan and its sophisticated electronics, so I left for here at 23 years old. At 26, although I was eight years older than the usual age, I was finally able to enter a Japanese university. I majored in electronics at the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, and also completed a doctoral course at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. However, I had already passed 34 years old by then, and was unable find a job in Japan. I could not give up on my dream of finding work here however, so in order to increase my employability, I worked like mad and obtained another doctorate. I had now earned two PhDs, but even then I was not recognized; to work so hard living in Japan for 14 years and still not be able to find work really put me at a loss. I decided at that point to rediscover my life; if Japan was impossible then this time I figured America was my only option. So at 38, leaving my three young children behind, I decided to have a go in the US scientific world, which I knew absolutely nothing about. With a spirit to ‘go for broke’, I decided to gamble my life one more time. Fortunately, I found a university that would recognize my talents, and was able to obtain my dream job as a teacher. I taught there for five years, but returned to Japan upon receiving an invitation from one of my old teachers at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, Professor Okujima.

Q:Why did you return to Japan from the US? Also, why did you start to tackle educational reform in universities?

A:I was trained in Japan, and as a result was able to earn 4 PhDs. It is thanks to the training I received in Japan’s harsh society that I am here today; I genuinely wanted to repay Japan for that. However, in my newly arrived university, I noticed that over 80 percent of students who did not understand their classes were just left that way, so I resolved to rekindle the motivation of all the students taking my classes.

I continued to encourage these students by talking about the actual experiences I had in my home country and in the US, and how I kept trying no matter how many times I was rejected in Japan. On the other hand, I adopted a very strict attitude in these classes. I conducted them mostly in English and also demanded students do presentations in English. In the beginning, students panicked, but once they learned how serious I was, they started to put more effort in. All young people are hiding possibilities (latent potential) that they themselves would not believe. It is the drawing out of this potential which is the serious approach of an educator. There is the idea in university that you should only deal with students who are motivated, but I refuse to abandon any of them. I also don’t want other teachers to abandon their students.

Invited the 100th anniversary of Chinese Univ.

Q:You did not experience affection in your childhood years – where does the unlimited affection for your students come from?

A:I think each student is the main character of their own stories. I want all of them to learn to like themselves and lead their own lives. In order to do that you cannot be half-hearted. My teaching is famous for being strict enough to make many students cry, but I absolutely will not let any of them give up on their dreams. Because their dreams are my dreams too.

Even students with seemingly no motivation hide wonderful possibilities (latent potential). For educators, it is necessary to have an attitude that seriously deals with these students’ true feelings, and strives to put every effort into teaching them. If you do this, they will definitely begin to regain their true selves, face their own dreams, and create their own stories. They will start to live their own original lives not created by others. This will then lead to greater self-confidence; students will gradually learn to like themselves and in no time will be become kinder to other people.

(photo :nikkie BP Mr sugano )

Q:Please tell us about your childhood and the details of how you came to Japan

A:Both my parents died when I was an infant, and I was raised by a very strict stepmother. With my weak constitution I was treated as a burden, so I have no fond memories of home. Being at home was unpleasant, so I began leaving early for school in the morning so I could help clean there. I started to be acknowledged by the teachers and everyone because of this; I then wanted to be acknowledged even more so I began to study harder and teach classmates and children in my neighborhood how to study. However, in 1965 when I had just started my first year in senior high school, the new government that had arisen out of the anti-Communist Party coup d’état (known as the 9.30 Incident) closed every school for Indonesian-Chinese children around the country, so we could no longer receive an education. I had no choice but to begin helping in my older brother’s business selling electronics, and while doing that I started my own repair business. Not only did that business become a huge success, my older brother was also able to lead a prosperous life, and it was from these economic reasons that I, despite being unable to go to high school and university, felt an uncontrollable urge to study more.

With my ambitions to become an engineer, I was naturally fascinated by Japan and its sophisticated electronics, so I left for here at 23 years old. At 26, although I was eight years older than the usual age, I was finally able to enter a Japanese university. I majored in electronics at the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, and also completed a doctoral course at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. However, I had already passed 34 years old by then, and was unable find a job in Japan. I could not give up on my dream of finding work here however, so in order to increase my employability, I worked like mad and obtained another doctorate. I had now earned two PhDs, but even then I was not recognized; to work so hard living in Japan for 14 years and still not be able to find work really put me at a loss. I decided at that point to rediscover my life; if Japan was impossible then this time I figured America was my only option. So at 38, leaving my three young children behind, I decided to have a go in the US scientific world, which I knew absolutely nothing about. With a spirit to ‘go for broke’, I decided to gamble my life one more time. Fortunately, I found a university that would recognize my talents, and was able to obtain my dream job as a teacher. I taught there for five years, but returned to Japan upon receiving an invitation from one of my old teachers at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, Professor Okujima.

Q:Why did you return to Japan from the US? Also, why did you start to tackle educational reform in universities?

A:I was trained in Japan, and as a result was able to earn 4 PhDs. It is thanks to the training I received in Japan’s harsh society that I am here today; I genuinely wanted to repay Japan for that. However, in my newly arrived university, I noticed that over 80 percent of students who did not understand their classes were just left that way, so I resolved to rekindle the motivation of all the students taking my classes.

I continued to encourage these students by talking about the actual experiences I had in my home country and in the US, and how I kept trying no matter how many times I was rejected in Japan. On the other hand, I adopted a very strict attitude in these classes. I conducted them mostly in English and also demanded students do presentations in English. In the beginning, students panicked, but once they learned how serious I was, they started to put more effort in. All young people are hiding possibilities (latent potential) that they themselves would not believe. It is the drawing out of this potential which is the serious approach of an educator. There is the idea in university that you should only deal with students who are motivated, but I refuse to abandon any of them. I also don’t want other teachers to abandon their students.

Invited the 100th anniversary of Chinese Univ.

Q:You did not experience affection in your childhood years – where does the unlimited affection for your students come from?

A:I think each student is the main character of their own stories. I want all of them to learn to like themselves and lead their own lives. In order to do that you cannot be half-hearted. My teaching is famous for being strict enough to make many students cry, but I absolutely will not let any of them give up on their dreams. Because their dreams are my dreams too.

Even students with seemingly no motivation hide wonderful possibilities (latent potential). For educators, it is necessary to have an attitude that seriously deals with these students’ true feelings, and strives to put every effort into teaching them. If you do this, they will definitely begin to regain their true selves, face their own dreams, and create their own stories. They will start to live their own original lives not created by others. This will then lead to greater self-confidence; students will gradually learn to like themselves and in no time will be become kinder to other people.

Ken Kawan Soetanto Professor, Faculty of International Liberal Studies

Professor, Faculty of International Liberal StudiesDirector, Clinical Education and Science Research Institute- Four doctorates: engineering, medicine, pharmacy, and pedagogy. I first came to Japan in 1974 as a university student and received doctorates in engineering and medicine. Recently I also obtained doctorates in pharmacy and pedagogy. Since my original field of study was medical engineering, which is an interdisciplinary field, it was natural for me to extend my area of interest. I did science and engineering research on health-related machines, and subsequently pursued clinical medicine studies of medical machinery. I extended the scope of my studies of medical machines from use in checkups to use in medical treatment, and in the course of my pharmaceutical research, I invented an ultrasonic contrast agent which received dozens of basic patents in Japan and two in the U.S.A.

International Students are precious to Japanese society

Q:The numbers of foreigners living in Japan has surpassed 2.2 million. How do you think Japanese society should respond to this from now?

A:I think Japan needs to take more care of their overseas students. A lot of Asian students are really studying hard while doing part-time work. I think for the future of Japan – as an advanced Asian nation – there is a need in Japanese society for adults to make these students feel really welcome. I worked as a teacher in America for five years; the secret of America’s popularity is its tolerance in accepting people from various countries. On the other hand, exchange students in Japan should learn more proactively about Japan’s great aspects. For example, there is no country with as little littering as Japan, and Asian students have much to learn from Japan about public morality.

For two and a half hours without a break, Professor Soetanto spoke to us in earnest, overflowing with passion. The students who participated in the interview were also completely drawn in to “Soetanto’s world”. Yet even the powerful Professor Soetanto has experienced poor treatment at the hands of Japan’s closed university system; twice he has had to return to Indonesia for convalescence due to the shock and subsequent depression he suffered as a result of that treatment. Yet despite those experiences he is still helping students in Japan in full earnest. His teaching technique - the ‘Soetanto Method’ - appeals to the spirit and is based on an educational attitude that ‘does not give up on any student’. It is having a profound impact on not just students, but also many instructors, and its effects are receiving widespread attention in both the education and business worlds. It is the sentiment from this one originally self-funded exchange student from Indonesia – that he would ‘never give up at any time – that is starting to change Japanese society.

Here at Global Community for this year, we will be introducing people who were able to pull themselves together and unleash their original potential through the Soetanto Method – stay tuned.

Students impression after interviewing Prof.Soetanto

(Right photo) Utano Suzuki (Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology)

I have had periods where I worried about the relationship with my mother and became emotionally unstable; there have also been times where I blamed my mother. However, this time I understood that I had been completely mistaken and felt very sorry towards my mother – I almost started crying. This is the biggest change for me. After meeting with Professor Soetanto and hearing him talk, it was as if the inside of me that I had kept shut up for so long had received a burst of fresh air. The cells inside my body which had been deprived of oxygen have come back to life. This has made me feel more powerful and energized; I want to direct this power towards my job hunting and English study.

(Centre photo) Makoto Arai (Daito Bunka University)

My impression after the interview was as if I had received a revelation. Professor Soetanto’s words, “You need fools for society to become better”, stand out in my mind. ‘Fools’ in this case are people who have love for others; people who can serve others. Also, from listening to Professor Soetanto – someone who has worked all around the world – I truly felt that Japan must rapidly advance its globalization. Through my current activities involving volunteer interpreter guiding and Global Community, I felt I wanted to create together a Japanese society which is both loved by people from overseas and where all people can live in harmony.

(Left photo) Ms Stintya (Lakeland College)

I felt very humbled by Professor Soetanto’s positive attitude to serve others. Exchange students in Japan tend to focus on Japanese society’s closed aspects, but I once again felt it is important to learn more from Japan’s great aspects. It was very encouraging think that someone like Professor Soetanto put himself through school as a self-funded student in Japan while working part-time, just like myself.

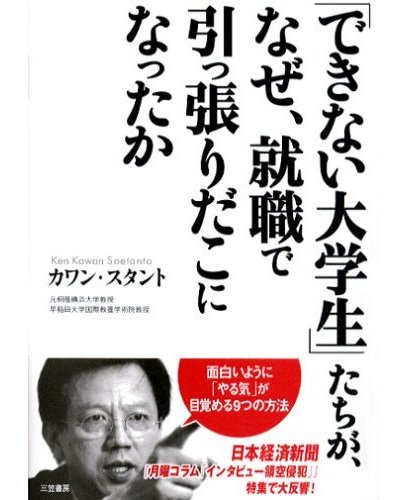

「できない大学生」たちが、なぜ、就職で引っ張りだこになったか

面白いように「やる気」が目覚める9つの方法

「できない大学生」たちが、なぜ、就職で引っ張りだこになったか

面白いように「やる気」が目覚める9つの方法

「負け組み」だと思っていた学生たちが、スタント教授の講義を受けると変わっていく。優良企業の採用担当者や、社長までもが、「おたくの大学生が欲しいのですが」とやってくる。あきらめない教育者の本気の姿勢が学生たちに本当の自分を取り戻させる。どんな状況でも生徒を信じてベストを尽くす魂に訴えるスタント教育法がわかりやすい事例で紹介されている。就職に悩む若者だけではなく、現役の教員の人たちにもぜひ、読んでほしい1冊だ。

《「できない大学生」たちが、なぜ、就職で引っ張りだこになったか

面白いように「やる気」が目覚める9つの方法》の評価をアマゾンで見てみる